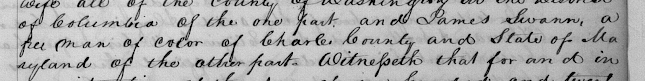

His name was Swann. James Swann. In 1843, when he was in his early 30s, he entered into an agreement with the Sheriburn family to buy a lot in Port Tobacco. Three years later, in May 1846, he completed the purchase when he bought out the heirs of the William Graham and took possession of an area of the town known as “The Point”. The lot came with at least one structure on it, which Swann was already occupying. On the face of it, there’s nothing remarkable about this – a man buys a town lot with a house on it. But there’s a detail in the 1846 deed that makes this purchase remarkable, it states that James Swan is “a free man of color.” By 1850, Swann and his wife Susan had established a tavern in the building.

Of the 30 households headed by a free man or woman of color enumerated in the Allens Fresh District in the 1850 census, only six housholds had real estate values included in their listing. They were the households headed by James Swann, Henry Swann, Henry Collins, Jack Boarman, William Boarman, and Hodena Butler. Henry Swann, Henry Collins, and the Boarmans owned farms in the area surrounding Port Tobacco. The Boarman farms were listed adjacent to one another and were valued at $100 each, Henry Swann’s farm was valued at $500, and Henry Collins’s at $800. Hodena Butler did not own real estate but her son James did. According to the census he owned real estate valued at $25; what this represents is unclear. As far as I can tell from the census, James Swann was the only free man of color to own property in the village of Port Tobacco. All of these men, with the exceptions of Jack Boarman and James Butler, are listed as mulattos. Jack Boarman and James Butler were listed as Black.

The 1850 census values James Swann’s real estate at

$500. He purchased the property for $225 in cash and the erasure of a $300 debt

owed to him by the heirs of Joseph Sheriburn (the former owners of the

property). The 1843 deed details the debt and the $100 cash payment Swann made to the Sheriburn heirs (Deed Book JB no. 25, folio 276). In

1846, Swann bought the interest of the remaining heirs to the property for $125

(Deed Book WM no.2, folio 29). So the value of the land in the census is close

to that of the purchase price of $525.

What did James Swann’s house look like? The Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties describes the house as:

This small but architecturally intriguing frame dwelling with quarried stone foundations faced north and was of one-story height. The three-bay facade featured a centered door, and a single exterior chimney with flanking pents stood at the west end. Of brick construction, the chimney and pents extended the full width of that elevation. The raised foundations enclosed a full cellar. A later shed addition stood on the south side.

Two possible photographs of the house show a frame, one and a half-story structure, with a large brick end chimney on the right side of what I assume is the front of the house. There is a porch, which does not extend the full width of the house. The front door is centered and has a window on either side of it. There is a tiny window above the porch and another one just off the left side of the porch. In addition, there appear to be ground floor windows on the rear of the house as you can see trees through the window on the opposite side of the house. There is also a window on the side of house that looks out over the chimney. The date of the two photographs is unknown, but my best guess would be in the early twentieth century after the town was all but abandoned. There is no information about who took the photographs, or who labeled them as the Swann House.

|

Robert Guy Barbour's Sketch of Swan House Reproduced by permission of Anita Barbour Gordon |

Complicating the matter is a sketch of the house done by Robert Guy Barbour in the mid-twentieth century that doesn’t match the photograph of the facade. Barbour grew-up in Port Tobacco during the early years of the twentieth century and the sketch is one of a collection he drew based on those buildings that were still standing and on his memory of the buildings in the town. His son, James Barbour, published a booklet of the sketches entitled Port Tobacco Charles County, Maryland Prior to 1895. I’ve used the sketches for several other projects in the village and to date I haven’t noticed any major discrepancies between period photographs and the sketches. But in this instance there is a disconnect. Barbour’s granddaughter Anita Barbour Gordon and I recently spent an afternoon comparing the facade photograph and the sketch. The sketch shows a one and half story building with a brick end chimney on the same side of the house as that shown in the photograph. There is a porch, but it extends almost the entire length of the house. The door is not in the center of the house, but instead is on the left side of the house and there are dormer windows in the roof. There is no indication of the latter in the photograph.

So the question is, did the photographer mislabel the photographs? Did Barbour draw a different Swann House that was in the village? Or is the problem related to the fact that there were two houses located in “The Point” area of Port Tobacco and the photograph and the sketch each show one of these two buildings? Neither Anita nor I have the answer to this puzzle. You can see the two buildings on “The Point” circled in red on the map below. We are currently excavating in the house area on the right, or so we think.

Which house we are dealing with - the photographs or the sketch - is one of the questions we will try to answer this summer as we excavate inside and around one of the building remnants identified as the Swann House. All that currently remains of this house are the stone cellar and the base of the brick end chimney that extends along the entire west side of the building. These remnants were located in 2009 during excavations by Jim Gibb and the Port Tobacco Archaeological Project. The foundation is rectangular, measuring approximately 32 feet east/west by 18 feet north/south. Gibb placed a unit in the northeast corner of the cellar during the 2009-2010 excavation season and encountered demolition debris mixed with twentieth-century items extending some 3 and ¾ feet below the ground surface.

This map was included in the 1945 article “Port Tobacco, Lost Town of Maryland” by Ethel Robey Hayden (Maryland Historical Magazine Vol XL:259-276) and is a reproduction of Robert Barbour's map.

The to scale drawing of the foundations was done by the Port Tobacco Archaeological Project in 2009.

So why bother with the rubble? One of the reasons is to determine when the building was demolished. The type of demolition rubble on the west end of the house indicates that the end chimney was dropped into the cellar. At the base of the rubble, and this position is important, we found fragments of two machine made 8 ounce A.G. Herrman soda bottles with a suction machine mark on the base. This means that they date no earlier than 1905 and as the Society for Historical Archaeology notes, it is more likely that these types of bottles occur after 1910 when Owens bottle machines and other automatic machines (which produce this mark) began to dominate the market. By 1917, 50 percent of the bottles made in this county had suction scars.

|

| Suction Mark |

When you add in the dates for land purchases, the demolition date for the structure becomes tighter. In 1914, Jennie Swann Blackburn (one of James Swann’s daughters) sold her share of the property to Adrian Posey. In 1920 (the year Pabst stopped brewing), Posey and the remaining Swann heirs sold the property to J. Perry Poole in a court mandated sale. Poole immediately sold the land to Henry Bush (he and his descendants owned the parcel until late last year). In all likelihood the building was demolished by Henry Bush around 1920. Bush and his family lived in a house along Chapel Point Road and not, as far as I can tell, in this house. Now we just have to figure out when the structure was built and which one of the images – photograph or sketch – is associated with the building.

I’ll add updates as we continue our excavation this summer, dive into the archives, and do some more oral histories. I’ll also talk about other questions we have about the house, about James Swann, and about the people who lived in the house before and after the Swann family.

For more information about dating bottles I recommend this site: Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website, which is hosted by the Society for Historic Archaeology and the BLM.

Comments

Post a Comment