|

| My favorite Ice Cream Place Labor Day 2023 |

The first Labor Day celebration

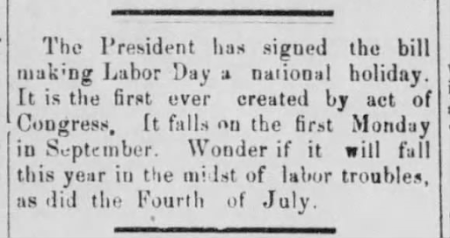

was sponsored by labor unions and was held on Tuesday, 5 September 1882 in New

York City. Over the next 12 years, 23 of the then 44 states adopted the holiday

as their own. The United States Congress voted to create Labor Day as an

official National Holiday in 1894, setting the first Monday in September of

each year as the holiday. President Grover Cleveland signed the bill into law

on 28 June 1894.

|

The Washington Times, 27 June 1894, page 1 |

Early Labor Day celebrations

in urban areas and small industrial towns included speeches and parades, with

the afternoon devoted to community picnics, amusements, and sporting events such

as baseball, for workers and their families. For my own family, who lived in

the coal towns of northeastern Pennsylvania, the holiday was a welcome break

from the 6 day a week, 10 hour a day work week in the mines.

.jpg) |

Coal Mining Crew in Plymouth Pennsylvania, early 1900s My great-grandfather George "Pop" Pickett is on the left in the back row |

|

Patuxent Oyster Co. Bucket Benedict, Maryland EBay |

The year that the national Labor Day holiday was created was also a year of strikes by the United Mine Workers and the various railroad unions. The latter began on 11 May 1894 when the Pullman workers walked off the job and were soon followed by other railroad workers. During June and July rail traffic, especially in the Mid-West, was severely disrupted. And violence erupted in industrialized cities.

|

Cartoon from the newspaper Chicago Labor, 7 July 1894 |

While it may not seem like the strike had much affect on Southern Maryland, it did. On 15 June, The Maryland Independent reported that work on the new Washington and Chesapeake Beach Railroad was halted and that a large number of workers were now unemployed. These workers weren’t railroaders, they were laborers (today’s construction crews). On 29 June, the same paper noted that the Southern Maryland Railroad was almost at a standstill because it couldn’t purchase coal to run its trains. On the same day, Colonel L.A. Wilmer of Charles County, Commandant of the First Maryland Regiment (National Guard), was ordered with his regiment to Frostburg to protect the mine owners and their property from the striking miners. Later in the year, an article in the paper discussed the need for cold storage as the few dairy farmers in the county hadn’t been able to get their products, particularly butter, to market before the goods spoiled (5 October 1894).

|

While Papers Associated With Labor like Chicago Labor Printed Cartoons Sympathetic to the Strikers, Popular Magazines Such as Harper's Weekly Saw the Strikers as Anarchists. |

The coal and railroad strikes affected agriculture and the industries in Charles County that needed coal to generate steam to run machinery and to fuel the railroads and steamships transporting goods to market. Then in the middle of the strike, President Cleveland signed the bill creating the Labor Day holiday. A few weeks later the 4th of July was marked by the strikes, causing the Maryland Independent to wonder on 20 July 1894, if the new holiday would also occur during the strike? But by late August, the strikes were over, just in time to celebrate the first Labor Day. For the first ten years, the Maryland Independent was less than enthusiastic in it’s reporting about the holiday and was certainly thinking in this vein about the first Labor Day when it quipped on 3 September 1894: “Monday was labor day - Labor has had sufficient rest for the past twelve months without the need of a special day or holiday. Don’t you think so?”

|

Maryland Independent, 20 July 1894, page 2 |

|

Maryland Independent, 3 September 1894, page 3 |

So

what changed the perception of Charles Countians toward this new holiday? If we track the changes in reporting

between 1894 and 1935, we can see how attitudes changed. I ran a search of the Maryland Independent for the term “Labor

Day” and encountered very few mentions between 1894 and 1905. The paper doesn’t

even mention the holiday in 1896, and in 1897 reports on it after the fact. It

noted that the holiday was proclaimed by Gov. Lowndes “but was given little

heed on the part of the country people who are too busy at this season of the year

to lose a moment’s work” (30 August 1897). Between 1897 and 1905 the paper, if

it bothered to include any notice of the holiday, simply stated that “Labor Day

will be Monday,” adding that the banks would be closed.

|

Maryland Independent, 30 August 1897, page 3. |

Things changed in 1906. The paper’s publisher was still Adrian Posey, a wealthy businessman, real estate developer, and local Republican shaker and mover; but the tone was different. The Maryland Independent started to report on what people were doing with their holiday. On 7 September 1906 the paper reported that people spent Labor Day at Marshall Hall, which was the location of a small amusement park and picnic grounds on the Potomac River. Steamboats brought excursions to Marshall Hall during the summer season that ran from Decoration Day (now Memorial Day) to Labor Day. Numerous items appear in the paper about Labor Day at Marshall Hall after 1906.

|

Image from Marshall Hall Historic Marker |

In 1911, the Maryland Independent reported that the Modern Woodmen (at that time a benevolent society) celebrated Labor Day at Chapel Point with “One of the finest and most enjoyable fish dinners ever held in the County…” The festivities included bathing and launch riding (8 September 1911). Chapel Point continued to be a popular place for Labor Day festivities. By 1915 the paper stated that “Labor Day was generally observed in the County.”

|

Bathing at a beach along the Potomac River in 1924. https://www.shorpy.com/node/3623 |

What caused the change? Part of it was a growing middle class in the county who had the time for leisure enjoyments. It became “fashionable” to spend the summer at beaches and amusement parks along the Potomac or, in the case of the upper middle class, at one’s country home. There people escaped the heat and relaxed until summer’s end on Labor Day. The holiday had evolved from a celebration of workers and labor unions to a day that marked the end of summer and leisure pursuits. It also became a day for shopping if you happened to be in a city or town with shops. While I didn’t find advertisments for Labor Day Sales in the Maryland Independent during the period 1894-1935, the Washington, D.C. papers were carrying Labor Day Sale advertisements as early as 1898.

|

Part of the Advertisement for the Lansburgh Furniture Company at 1226 F St. NW The Washington Times, 4 September 1898, page 2 |

The white middle class wasn’t the only group celebrating Labor Day. On 28 August 1914, the Maryland Independent announced that the African American congregants of St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Bryantown would hold their Grand Tournament and ball on Labor Day. An advertisement in the paper in 1916 for the Labor Day event at the church grounds included tilting (i.e. jousting, our official state sport), a brass band, dinner, supper, and ice cream (1 September 1916).

.jpg) |

Maryland Independent, 1 September 1916, page 3 |

|

| Maryland Independent 22 August 1919, page 3 |

|

| Maryland Independent 3 September 1920 |

Advertisements for Labor Day entertainments appear in the Maryland Independent each year after 1919. These include church sponsored dances, picnics, and dinners. In 1921, the American Federation of Labor held a barbecue at Marshall Hall. And in 1924, the paper noted the “Many city folks visited our summer resorts Monday last - Labor Day” (5 September 1924). The holiday had become a way for churches to raise money and it had invented a new industry for the county – tourism.

Advertisements for destinations outside of Charles County begin to appear in the paper in 1923. The Pennsylvania Railroad System encouraged people to “Enjoy a real vacation over Labor Day at the seashore” in Atlantic City (24 August 1923).

|

Maryland Independent, 24 August 1923 |

From the 1920s through the mid-1930s, the third page of the Maryland Independent carries advertisements not only for Labor Day but for a cornucopia of dances, picnics and events that bracket either side of the holiday. The “country people” of Charles County had gone from being “too busy at this season of the year to lose a moment’s work” to enjoying the fruits of their labor.

Comments

Post a Comment